THE MYTH: Any time you sustain an injury or have pain in an area, the old acronym R.I.C.E. (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) will help the healing process and get you back in the game as quickly as possible.

THE REALITY: R.I.C.E. is an antiquated methodology that often does more harm than good.

All day long in my Austin clinic, I hear the four-letter word — well, lots of four-letter words, actually, but one stands out: pain. Most of us are afraid of it. We avoid it at all costs and consider pain a big red flag that we are doing damage to something and we need to stop.

The aversion to pain is one of the biggest limiters I see both from a rehab standpoint as well as a performance development perspective, and the rehab world continues to grasp onto this “avoid painful activity” paradigm for fear of aggravating a patient’s symptoms.

Don’t get me wrong: it’s not advisable to run immediately following a major injury (something like a hamstring avulsion, tibial stress fracture, or torn meniscus) but it’s also not advisable to stop loading those structures all together, even if it causes pain! Most injuries are much less severe than those mentioned above, and yet the medical community’s standard advice is typically to:

- Stop running.

- Rest, Ice, Compress, Elevate (R.I.C.E.)

- Tape it up.

- Manage the injury (and, of course, the pain) with analgesics, anti-inflammatories, muscle-relaxers, and cortisone shots.

At RunLab, we have always taken an active care approach to rehab, even at the risk of increasing a patient’s symptoms for the greater good. I almost never tell someone to stop running unless the injury is extremely severe; even then, I advocate for a rehab plan that includes loading. More and more research is coming out that shows our old way of doing things in the rehab world just doesn’t work. Even Dr. Gabe Mirkin, who first coined the R.I.C.E. acronym in 1978, recanted his position on rest and ice in light of an onslaught of evidence showing that it actually causes delay in healing.

Research shows ice can cause decreased release of IGF-1 (a growth factor released by macrophages to help “clean up” damaged tissue); constriction of blood flow to the injured area (the effect we THOUGHT we wanted but now realize can be damaging, especially if ice is used on an area for more than 20 minutes); and reduction in strength, speed, power, and agility immediately after use.

Food for thought: consider how this affects an injured athlete trying to get back on the field as he sits on the sideline with a huge ice pack on his knee until it’s numb enough to get back in the game. He re-enters the match with decreased coordination and agility, which is a recipe for disaster when it comes to sports like soccer, football, rugby, and pretty much everything else involving lateral movement.

Many of the most frustrating injuries are those that occur in areas with poor vascular supply: high-hamstring strains, Achilles tendinopathy, ITB syndrome, etc. Many patients end up spinning their wheels on the massage table, foam roller, etc. to find only temporary relief with these passive modalities. Slow progress in healing these injuries is often multifactorial, but fear of loading the injured tissue can often delay the healing process even further.

MEET JOHN

A patient, we’ll call him John, is an avid marathon runner and injures his hamstring at the insertion point (sit-bone) while doing speed work at the track one day. John has pain with both walking and running and is told by his primary care doctor that he should take time off from running and all weight bearing exercise until the pain is gone. He complies with his doctor’s orders, ices the area a couple of times per day, downs a few Ibuprofen each morning, foam rolls the area like crazy, and sits around thinking about running, how fat he’s getting, and the marathon he has in eight weeks.

(Note: You do not, in fact, get FAT by taking one day off from running. I’m looking at you, every runner in the history of ever.)

Since John’s doctor told him to take two weeks off, he waits four full days (!) before deciding to “test it out.” It feels OK for the first few steps as he gingerly shuffles along, but then the familiar tugging starts as soon as he tries to dial up his pace. He tries to shorten his stride so it doesn’t hurt. This helps a little and he is able to shuffle along for a couple of miles before his calf starts giving him trouble. He stops and walks back home, frustrated.

John takes a few more days off but cannot stand it anymore and tries to run again on his next day off work (where he spends all day sitting at a computer). As soon as he begins running, he feels pain in the hamstring, but he’s able to shift his gait again and get a little farther this time. Progress! He comes back from a three-mile run and is finally happier mentally, already looking at his calendar and counting how many runs he can get in before his marathon.

He continues to foam roll, starts stretching the hamstring a billion times a day, and continues to increase his mileage as he keeps his stride super short to avoid irritating the area. He limps along like this for another month, and races the marathon with a disappointing slide into run/walking by mile 16. By the end of the race, his hamstring is worse than ever and his Achilles tendon is now aching consistently. He ends up back in the office of the MD, who now sends him to physical therapy, where they focus on stretching, foam rolling, clamshell and other antiquated hip exercises to strengthen the “glutes that aren’t firing” (an entire blog post for another day).

John is told to avoid all exercises that increase his pain, including running. After three months of physical therapy, daily foam rolling, a few chiropractic adjustments to (realign his hips and pelvis, several rounds of kinesiotaping, daily ice packs, a few hundred miles on the spin bike to kill the demons — he tries his first run. He feels great for about two miles and then guess what?

You guessed it. More of the same. Sound familiar? Most runners have struggled with something like this, whether it’s a hamstring, patellar tendon, plantar fascia, the IT Band, or any number of other problem areas.

So what are we doing wrong in the rehab and training world?

Many may disagree with me on some of the following points, and that’s OK. There isn’t enough research out there to definitively tell us how best to treat our runners 100 percent of the time. One thing we do know is this: our old methods don’t work and we need to stop being afraid to change.

After treating thousands of runners over the last decade, here’s what I have found to be consistently true:

Tendons are meant to be loaded.

Is it going to cause pain if the tendon is injured? You betcha. Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily. A systematic review published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine reiterated what many forward thinkers in the rehab world have suspected for years: pain-inducing exercise can actually speed reduction in symptoms over non-pain-inducing exercise as it relates to chronic musculoskeletal injury. More research is warranted in this area, but evidence is starting to solidify the idea that pain should not always be used as the overarching guideline for rehab, strength training, or injury management. Should this knowledge be exercised with caution and only under guidance from someone who is going to make sure you crazy runners don’t go out there and rupture your Achilles tendons because “if a little pain is good, then a lot is REALLY good?” Yes, obviously.

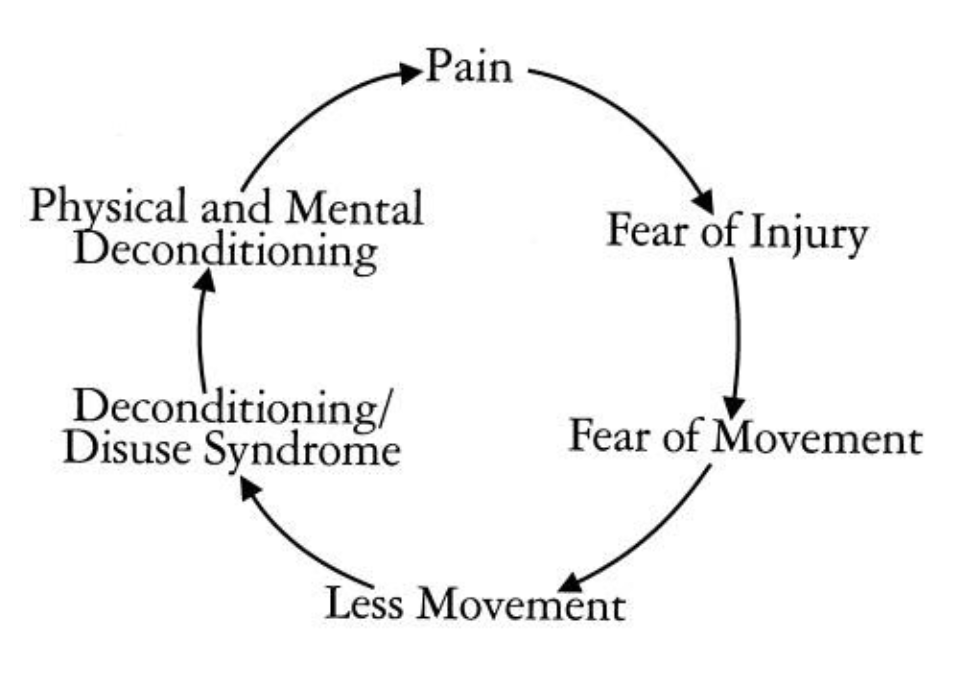

Fear-avoidance behavior can be more damaging to movement patterns than the injury itself.

I have seen many runners who end up sidelined two years after a minor injury because they are so afraid of doing more damage to the area that they avoid any movement or activity that increases their symptoms even temporarily. This leads them down the biomechanics corridor of death in terms of movement patterns. Compensation pattern after compensation pattern is developed, only to create a snarled, layered biomechanics mess that can be extremely difficult to unravel years later.

The body is meant to run.

Running is an activity of daily living. If you can’t sprint to catch the bus because your knee will hurt for three days, then that is a serious problem. Wait … is riding the bus still a thing? I should say, if you can’t sprint to catch your Uber driver when you realize you weren’t paying attention and had gotten into some random person’s car, then THAT is a problem. Not saying that’s ever happened to me …

R.I.C.E. is largely crap, but why?

REST? Completely resting an injured area for any length of time is a sure-fire way to decondition the entire kinetic chain and create long-term problems. Reintegrating injured muscles into their normal functional movement should begin immediately following injury.

ICE? It doesn’t help healing in most circumstances, it delays healing, decreases coordination, agility, strength, and endurance. What is a better “I”? Start the isometrics as soon as you can weight bear.

COMPRESSION? Sure. Doesn’t seem to do harm, but more research is certainly needed on whether those really cool looking compression sleeves actually do anything significant beyond covering up your giant Ironman tattoo. I jest, I jest! I did triathlon for years, and as an official drinker of the Ironman Kool-Aid I never miss a chance to tease my fellow triathletes about the tattoo obsession.

ELEVATION? Sure, OK. Assuming you have so much swelling that you need that edema flushed back toward the heart and to stop pooling int he extremities. Otherwise, once you can tolerate isometric exercise and loading, start there and then progress slowly to eccentric exercise geared toward strengthening muscular control during the gait cycle.

Running through injuries is often OK.

Assuming the injury doesn’t involve, say, a fractured bone, running can often be incorporated into a rehab program. Even a fractured bone needs loading or it will end up deconditioned AND osteopenic, it just needs to be loaded carefully and under the guidance of someone who understands biomechanics at a high level. Remember Wolff’s Law? Pressure on bone builds more bone. Active recovery in a functional environment is, in my opinion, the best thing that can be done for an injury. The sooner the injured tissue can get reintegrated to do its job within the context of the kinetic chain, the less chance there will be for developing scar tissue and compensation patterns.

Also if you have a fractured bone but a bull is chasing you? Probably still OK to run. 🙂

SUMMARY:

- Pain is not always bad and may even be beneficial in certain circumstances.

- Loading is good for muscles, tendons, and bones and should be an integral part of all rehab and training — under supervision.

- Stop RICE’ing everything! No, really.

- If a doctor tells you running is bad for you, find another doctor.

- When you injure yourself, get guidance from someone who looks at the whole kinetic chain and treats you as a unique individual. There are a lot of great therapists and trainers out there, but you have to do your research. We have some great partnerships around the country; call us if you need help.

Thank you for taking the time to read our RunLab™ Blog! We hope that you use this information to run more injury free and to optimize your running performance.

For more information about the RunLab™ team and to get your running stride analyzed by one of the preeminent gait specialist teams in the country, please visit WWW.RUNLABAUSTIN.COM

Outside of the Austin area? You can still have your running stride analyzed by one of the best teams in the country. Just visit WWW.RUNLAB.US to see where our partner filming locations are based or choose the self-film option.

RunLab™. Helping runners help themselves.

ABOUT DR. DAVIS

Dr. Kimberly Davis is the Founder & CEO of RunLab™, a motion analysis and gait diagnostic company headquartered in Austin, Texas that provides runners anywhere in the country access to comprehensive gait evaluation services through www.RunLab.us. An Ironman triathlete and ultra-distance adventure racer herself for over 20 years, Dr. Davis has dedicated her career to the study of clinical biomechanics and helping runners get back on the trails, improve their performance and enjoy running again. Working as part of sports medicine teams for over a decade, she grew tired of hearing her patients say they had been told not to run or that “running is bad for your knees” by their doctors without any discussion about biomechanics. She launched RunLab™ Austin in 2014 as a running-centric healthcare facility built entirely by, and for, runners. It has since grown to become one of the nation’s preeminent gait evaluation and training facilities in the U.S. Working with every age and experience level runner, from Olympic gold medalists and world champions to brand new runners, kids, and runners with special needs such as down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and a wide variety of movement disorders. Recognizing a lack of consistency and quality in gait analysis across the country, Dr. Davis launched RunLab.us in 2018 as a means for runners to access her industry-leading gait team from anywhere in the United States.

LEARN MORE:

RunLab™ Podcast RUN.

RunLab™ YouTube channel